- The Moral Universe

- Posts

- Very Guilty, Not Ashamed

Very Guilty, Not Ashamed

If you are able to choose, it is better to feel guilt not shame

"Catch flights, not feelings" is the motto of a generation of losers. To be more precise, that of the millennials, which happens to be mine. However, I have always despised that saying, which has never truly fit me. I am more prone to experiencing heightened feelings precisely when I am on a flight than anywhere else. There must be something about the lack of Wi-Fi on the flights I take and the subsequent freedom from distractions.

In the past few months, I have often travelled around opposite poles of Europe for work. You would think that at such a stage of globalisation, working in intercultural teams would be smooth sailing, but it often proves to be a bumpier road than expected. Different cultures mean different value systems and different ways of communicating them. Navigating all of these differences while working towards a common goal is far from easy.

So today, as I find rest in my assigned seat on a flight from Milan to Brussels, I am finally finding time to write a reflection on this topic. Two players seem to move us like pawns: shame and guilt. How do shame and guilt shape our lived experiences? And is one of the two leading to a more moral life than the other? These are the questions I am battling with whilst the person sitting next to me is about to fall asleep on my shoulder.

This is not the first time I have asked myself this question. As an Italian-Albanian growing up between cultures, I often wondered which way of dealing with life was the "right one". Being a migrant means being a shapeshifter of morality. Was it better to feel shame on such a frequent basis, as my Albanian identity demanded, or to give in to guilt like the Italian one suggested? At 30, I might have found my answer.

Guilt vs Shame: Similar, but not the same

In principle, both guilt and shame are self-conscious emotions. In fact, they resemble each other so much that we often confuse them. Both lead us to scrutinise ourselves and our actions. And yet, if we examine them closely, the result of this scrutiny leads to living two completely different types of lives.

The American social anthropologist Ruth Benedict was one of the first to popularise the idea of a separation between shame cultures and guilt cultures. In 1946, she compiled "The Chrysanthemum and the Sword: Patterns of Japanese Culture", an analysis of Japanese culture during World War II for the U.S. Office of War Information. The study became a medium for US citizens to learn more about Japanese culture. And surprisingly enough, the book became even more popular among Japanese people seeking to understand themselves from an outside perspective.

There is a third way. Benedict mentions the option of a "fear culture", but it is a component that, in my opinion, makes little to no sense. When you feel shame, you live in fear that others won't accept you, that you will be ostracised for who you are. When you experience guilt, you live in fear of not being able to change the effects of what you have done. Both feelings are encapsulated in fear itself. Fear is their soil. I know this well because I have lived between two cultures that face each other and yet are so different in what controls their actions and their morality. From the Apulian coast, a guilty Italian can admire the peaks where an ashamed Albanian is resting.

shame noun

an uncomfortable feeling of guilt or of being ashamed because of your own or someone else's bad behaviour

My morality was first shaped by shame. At the breakfast table, all my family would gather and recall the dreams they had. All generations lived under the same roof. As a child, I remember holding a feeling of suspicion while watching these adults invent elaborate dreams that I felt they had not had the night before. I could see they were trying to communicate their true feelings to others through those invented dreams. They could not muster the courage to openly communicate their realities.

I also recall that at some point, my male cousins went through a circumcision ceremony, and for a week, they were treated like kings and covered in sweets and money. I was a justice warrior before it became a trend, and one day I decided to simply announce at the dinner table that I wanted to get circumcised too. It was unfair that I did not get the same treatment as my cousins. Back then, in my family home in Albania in the early 90s, women's tables and men's tables were separated, and children ate at a separate table. There was a hierarchical structure even in how our meals were consumed. And there I was, a 5-year-old girl asking to get circumcised in front of the entire family. My mother rushed to shush me, my grandparents were ashamed, and my older cousins laughed about me, not with me.

I must have seemed like an alien—a young child talking about private parts that were not even her own, in a family where sexuality was banished from any discourse and where men and women lived very different lives, with very different sets of freedoms and responsibilities. Girls were not allowed to marry whom they loved. Dating was not contemplated. They were instructed that "they would learn to love the man chosen for them."

In that context, shame was a way to preserve honour. Honour, your family name, and the way you carried that name meant everything, although we did not have anything material at that time. "Name" was built on how generous and useful one was to others. The "other," in a shame culture, is omnipresent and despotic. Every person who has lived long enough in a shame culture has heard one time too many the phrase "what would the neighbours think?"

We prized honour so much that we made sure to preserve the honour of those we encountered and respected, too. When we would go to visit a relative or a family friend, we would perform a sort of ritual that looked silly to my child's eyes. They would offer us pastries and juices, and we would reject them. And they would keep asking us, and we would keep firmly rejecting. I remember I so wanted to get my hands on one of those pastries, but I had been instructed before leaving home that I had to refuse at any cost.

After the fall of the communist regime, we were not only very poor but also living in times of great uncertainty and turmoil. Food was scarce, and so we tried not to be a burden to those we visited while still allowing them to display generosity. It was pretence that guarded everyone's pride. We all left hungry but with our "face" intact.

Honour/shame cultures are generally collectivist. The issue isn't right or wrong but honourable or dishonorable. Acquiring honour and avoiding shame are the highest goals. Self-expression and fulfillment are less important than group success and honour. Shame comes from failing to fulfill the group's expectations. Individuals sacrifice for the good of the team, family, village, or country. Communication is indirect, and body language communicates feelings. Therefore, the unspoken is as significant as, if not more significant than, the spoken.

What I take away from the shame culture I grew up in is that shame does not judge your actions solely; shame makes you think you are inherently wrong as a person. As such, shame is a blocker. It is far more pre-emptive than guilt. Sometimes the fear of being judged wrong prevents us from doing anything at all. If you think that not only what you have done is wrong but that you, the person who took those actions, are wrong, then the magnitude of change you need to be able to perform can engulf you in despair. As such, one ends up in a performance for the audience—the community. Are you truly a moral person despite the spectator presence, or are you moral just because you are being watched? That has been a doubt I have had about many people.

Another realization is that in a culture of shame, humour is restricted. Humour is inherently based on truth. It is about saying the truth in a way that does not sting, not at first, at least. In a culture where pride and honor are everything, letting ourselves enjoy the vulnerability of a joke is seen as too risky. Therefore, we conceal and we evoke.

guilt noun [ U ]

a feeling of worry or unhappiness that you have because you have done something wrong, such as causing harm to another person

In essence, guilt is feeling bad, to different degrees, about something we have already done. Guilt is the by-product of that action. Most guilt/innocence cultures are individualistic (i.e., Western). We measure everything with the yardstick of right and wrong. We make laws that determine innocence and guilt. Knowing and exercising individual rights is a primary concern. We teach children to be law-abiding and expect them to develop a conscience. We define innocence as being right or as righteousness. People feel guilty for what they have done or have not done. Communication is direct; confrontation is acceptable.

As such, the first cultural shock I experienced when I arrived in Italy at age six was when I was asked if I wanted a panino with prosciutto cotto, and I said "no" to keep up with my ritual, and nobody kept insisting that I have the panino, so I ended up not having any. That lesson stung in my stomach. "In this culture, they are not performing", I thought, "I have to be clear about what I want and say it straight away". The second shock was that the neighbours would struggle to even say "Buongiorno", let alone have a care in the world about what we would do or not. The third was that these people talked a lot about their own "happiness", which was not high on the agenda in the shame culture I came from.

When I think of guilt, the first images that come to my mind are connected to Catholicism. I think of Jesus, of Judas, of the need to repent, to repair, to make amends. I think of myself as a "know-it-all" teenager being interrogated by my English teacher for an hour. She had given us a paper to write about the job we wanted to do when we grew up. As I had no clue, I decided to write it on the job I'd never do. I figured she wanted us to practise our written English and that she wouldn't mind. Indeed, she did not mind at all about the diversion, but, boy, she minded about what I had written, and she wanted to give me a lesson, one that was not necessarily about English grammar. I had written a two-page essay about how being a lawyer was an immoral profession because you had to defend literally anybody. In retrospect, she wanted to teach me that everyone deserves defence, that everyone is innocent until proven guilty, and that I was being too unforgiving. In retrospect, I judge myself as having been very judgmental. I came from a culture that defined people by their errors for a long time, which is why people were very often so petrified of being wrong that they would often prefer inaction to mistakes.

Guilt leads to corrective measures that are not only dictated by the look of others, by the need to be accepted by the collective, although that acceptance might cost your true self. Guilt is less fake.

If anything, be guilty more than ashamed

In an ideal life, we would live devoid of fear. A life without fear is a life full of freedom. A life of freedom is a life full of responsibility, too. A life of freedom is one where a person has agency over their own life. Guilt and shame fill people with fear.

And yet, if I had to choose which one to feel, I would choose guilt over shame any day now. Guilt is the lesser evil. Allow me to think as a novelist for a second. Although the thought of having a daughter who is a writer instead of a doctor would make my Albanian mother ashamed. But, I think, if we were to think of each person as a character in a novel, shame would write a rather boring novel compared to what guilt could inspire. The character arc inspired by shame would be short and not nearly as interesting as the one inspired by guilt. Shame would have our character repress itself to the point of inaction. It would silence our protagonist, who cannot even think of himself as a possible hero. Too busy licking the wounds of being somewhat inherently flawed, and not simply a person who did something wrong.

Guilt, instead, is another story. If guilt is truly felt and teaches the person something, it is the start of a journey of transformation that has been at the basis of pretty much centuries of art and literature in the Western world. Guilt inspires action, and at its basis, there is a possibility of forgiveness and therefore hope.

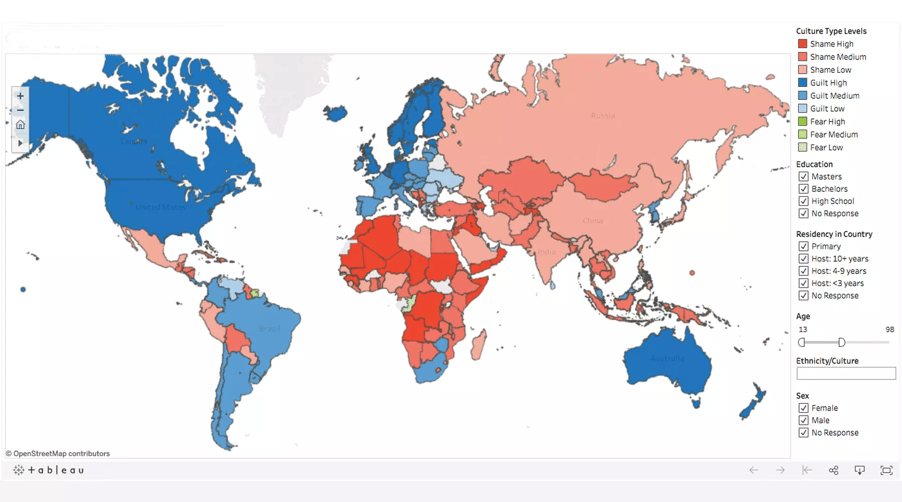

If we carefully look at the map, only 30% of the world seems to be guided by guilt instead of shame. Those areas coincide with the richest nations on the planet. And money, to many, is about freedom.

Vilma Djala is currently Education Lead at EIT Digital, the European Institute for Technology. She writes a weekly personal diary/newsletter: https://substack.com/@thecontrarymary that is inexplicably read across 52 countries.

Reply